(main menu)

CAMPBELL

articles

SITEMAP

site is

ABOUT

NEW

|

(main menu) |

CAMPBELL articles |

|

SITEMAP |

site is ABOUT |

NEW |

|

However, minor corrections have been made and some material (omitted from the original because of length) has been added. Such sections, and later additions, are indicated by { }. An extended passage has also been introduced from the Geographical Magazine article. The result is an unpolished text designed to set down all that has been discovered to date, with pointers for future research.

Because the atlas and this interpretation were never published - largely the result of an abortive attempt to produce a facsimile with commentary - Llewellyn's atlas has hardly been mentioned in print since 1975. It is hoped that this web-mounting exercise may reverse that neglect.

The 1975 text acknowledged the assistance of the librarian of Christ Church, Dr J.F.A. Mason, and the Archivist of St Bartholomew's Hospital, Dr Nellie J. Kerling. To those should be added thanks for the help on English charting of the period provided by Sarah Tyacke and to Katie Ormerod, Deputy Archivist of St Bartholomew's Hospital, for details about the crucial meeting in August 1597 (2009).

Use may be made of the text, with appropriate acknowledgement please, including the note of its creation date.

|

I would be happy to receive comments and corrections: |

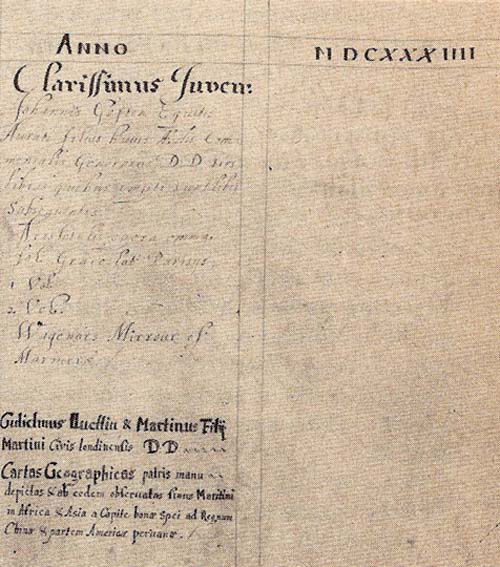

| Martin Llewellyn's sons gave his sea atlas of the East to Christ Church, Oxford, in 1634 and it remains there to this day. The event is recorded in their Donors' Book |

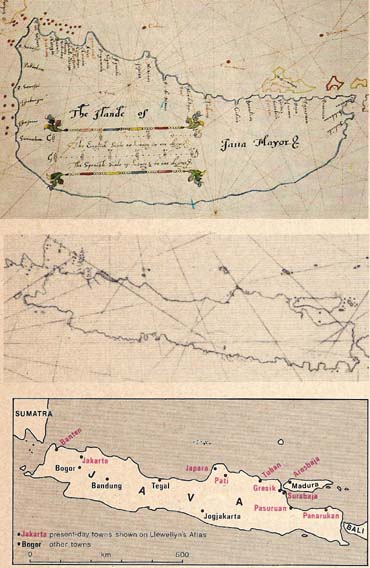

Llewellyn's atlas was donated to Christ Church in 1634 {though a former Librarian thought this event might have taken place anywhere in the period 1632-39, in which case Martin Jr's evident arrival in 1636 might be a possible alternative date} . The entry recording this gift states that it was "drawn in [his own] hand and according to his own observations", from which it seems that Llewellyn had himself travelled to the East. It can be shown that he was in one continuous occupation from 1597 until his death in 1634, as Renter, and two years later, Steward, of St Bartholomew's Hospital, London. He could not, therefore, have left England on an extended voyage after 1597. Corroboration that he had indeed drawn the atlas himself comes from the clear evidence of the same hand on some estate plans prepared for the Hospital, for one of which there is a record of payment to him. The investigation which this paper describes has uncovered the fact that the first Dutch voyage to the East (1595-7), under Cornelis de Houtman, led to the introduction of an entirely new range of names for the East Indies, and particularly for Java. The 32 names added to its north coast include today's capital, Jakarta and Surabaja, now the second-largest city. The source for these can be identified with confidence as Pedro de Tayda, a local Portugese pilot living in Bantam. De Tayda was able, in the course of the three weeks between the arrival of the Dutch and his own murder as a consequence of that contact, to pass on his cartographic knowledge of the East Indies. Llewellyn's atlas includes many of what can be recognised for the first time as place-names deriving from de Tayda.

Only the voyage undertaken by Houtman could have been completed by the time Llewellyn took up his stewardship and, simultaneously, have provided his Java toponymy. The likelihood is that he himself was one of the eighty-nine survivors of that expedition (in which case, as a foreigner, he might well have disguised his name) and that his atlas represents knowledge of the period immediately prior to the foundation of the East India Company in 1600 and of the Dutch equivalent (VOC) in 1602. Among leads suggested for possible future research are the connections between the chronically debt-ridden Llewellyn and various wealthy and influential individuals, including some (his brother among them) involved with the earliest history of the East India Company.

|

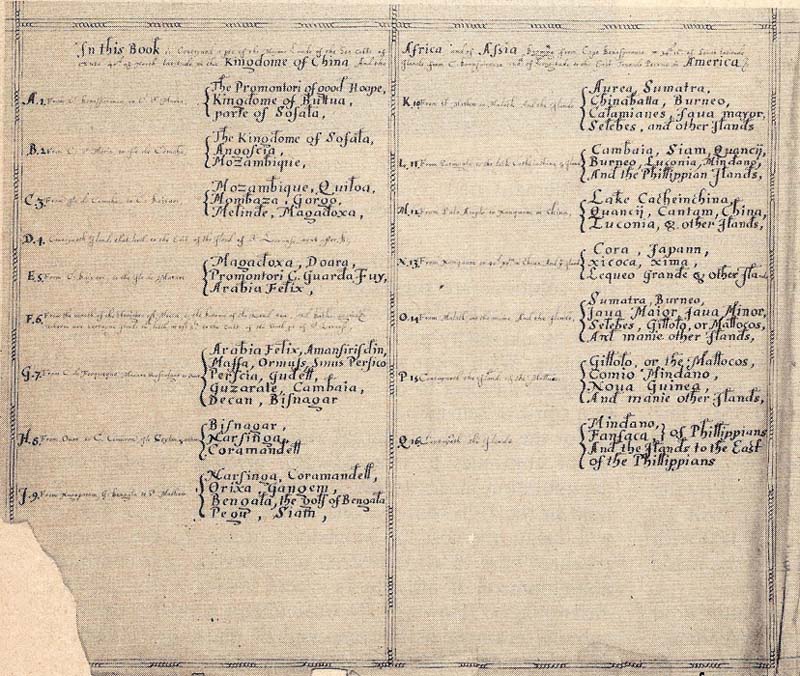

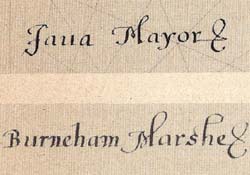

The list of charts in Llewellyn's own hand |

{Attempts were made to identify the watermarks in the title sheet at the front and the blank end-paper at the end. While they appear similar, and each is made up of joined sheets of the same paper, the marks are different front and back. Neither watermark could be found in Bricquet or Heawood although there were similar marks (French or Italian) from the later 16th century. The closest match (on the end-paper) was with Heawood 2133, reported from the 1616 edition of Speed.}

The atlas is preserved in a full calf binding, die-stamped on both covers. It is undoubtedly the original binding and is typical of English work of the early 17th century. {The fact that a few of the charts have had a part of their border trimmed away confirms that the charts were bound up after they were drawn. However, the title sheet, neatly ruled into quarters, whose precise size depended on that of the bound volume, must have been completed after binding had taken place. There are presumably four stages to be considered: the rough compilation of the charts, the fair drawing of those charts, the binding up of the volume, and the writing out of the title. These events could have been separated by years. }

The volume is in as good a condition as could be expected; there is no trace of any water-staining that might point to use at sea.

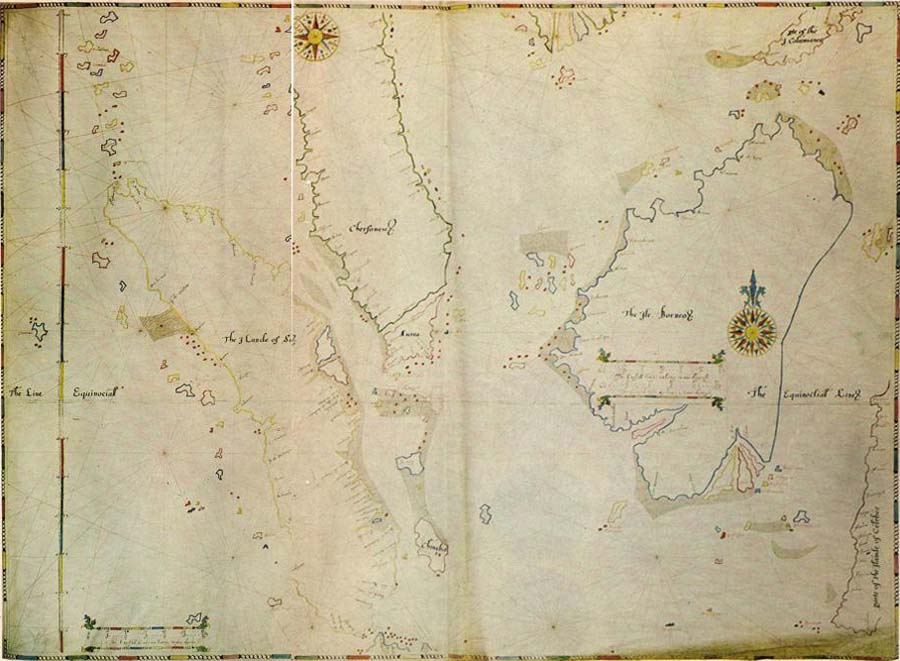

The sixteen charts extend from the Cape of Good Hope to the Far East, including Japan, the Philippines, the Marianas and the north-western part of New Guinea. {The reference in the Christ Church Donors' Book [see Analytical methods] to 'partem Americae peruanae', might be taken to indicate that part of America was included. Rather this states that the charts extend to China and then 'towards South America' - somewhat misleading given that Japan is the eastern limit}. They are projectionless plane charts with latitude scales, and with slight overlap from one chart to the next. From the duplicated sections, it is evident that the coastal outlines were traced from a common model. Repeated names, however, were treated in the cavalier fashion of the period and frequently differ from one chart to the next - for example Tornoall and Toronal, Tydor and Tichor, Maycan and Macan [charts 10 & 16].

[A slightly amended passage extracted from 'Atlas Pioneer', Geographical Magazine 48:3 (December 1975), pp. 165-7 - any extract from the indented section below should be separately acknowledged]Until the first Dutch and English fleets appeared in the Indian Ocean at the very end of the 16th century the Portuguese flag was the only European one seen in the East Indies. From this commercial monopoly it followed that the Portuguese hydrographers were the only ones who had access to first-hand information about the islands and harbours beyond the Cape. Their jealously guarded charts - always kept in manuscript and never printed - played an essential part in keeping out intruders. Portuguese charts of the 16th century varied considerably but they were usually on a relatively small scale, ranging only from eight to ten millimetres for 10 degrees of latitude. Llewellyn's charts so far break with this tradition as to quadruple the scale to thirty-eight millimetres for 10 degrees [very approximately 1:3 million]. Also unusual is the fact that this scale is constant throughout his atlas. The sixteen charts that Llewellyn needed to cover the known world east of the Cape of Good Hope normally fill only five, much smaller sheets, in the typical world atlases produced by the most prolific of the Portuguese chartmakers, Fernão Vaz Dourado [for all matters relating to Portuguese output see PMC].

If Llewellyn's atlas was constructed about 1598, and this seems the most likely date in the face of the evidence available at the moment, we have to look for a Portuguese source for those areas not affected by the first Dutch voyage, or else admit that his work is original. If the use of a scale not paralleled in the entire surviving Portuguese output hinted that there might be difficulty in finding the model for his charts, the further the investigation proceeded the clearer it became that Llewellyn's source, whatever it might have been, has not survived. The outlines he gives to the islands in the East Indies, for example, find no precise equivalent in Portuguese work.

But more striking still are the peculiarities of his style, for these serve to mark him out, not only from the Portuguese and Dutch chart makers working at the turn of the century but also from his English contemporaries.

Chartmaking in England was still in its infancy during Elizabeth I's reign. But there were a number of people working close to the Thames to serve the needs of English mariners: John Daniel, Thomas Hood, Thomas Lupo, Robert Norman, Richard Poulter, Nicholas Reynolds and Gabriel Tatton. One of these, John Daniel, was to found a school of chartmakers, all of whom were apprenticed in succession into the Drapers' Company of the City of London, thus perpetuating certain distinctive features of style [Campbell; Smith; Tyacke]. Had Llewellyn been apprenticed to any of the known Elizabethan chartmakers, or even taught on an informal basis (since he was evidently a 'gentleman' rather than an artisan), we could have expected some traces of their style to recur in his work. Instead, it is so totally different from all of them that it seems inconceivable he could have been taught by any of the chartmakers already known to us. Yet the method by which he constructed his charts and the way he conveys his hydrographical information show him to have been in the mainstream of the portolan chart tradition.

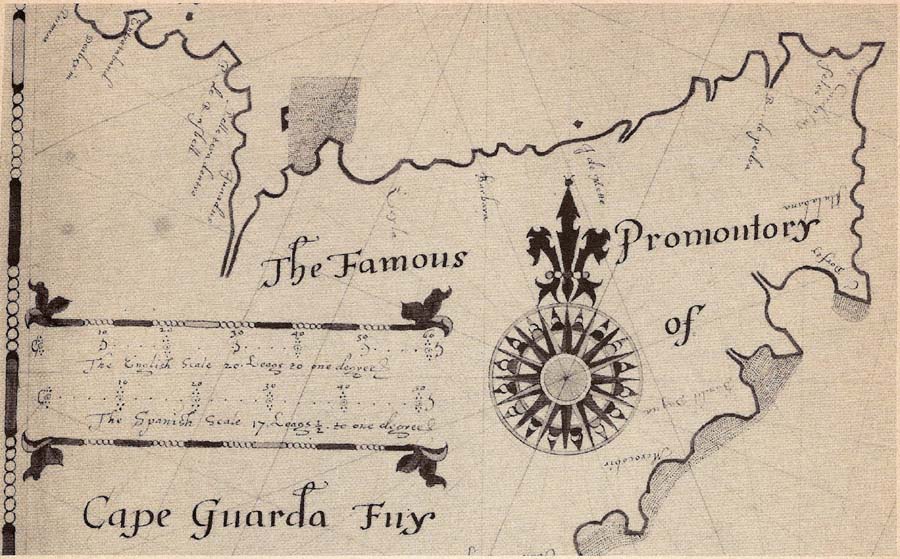

To start with, his palette is unusual. The five brightly preserved colours which he used include a surprising mauve and untypical tones of red, yellow, green and blue. Then there is the continuous border, repeated in the surrounds to his scale bars. This device, ancient Greek in origin, seems intended to represent a chain of beads. It is found also on the engraved maps of Ortelius and Mercator, as well as on Waghenaer's printed marine charts [1584 onwards], which Llewellyn would presumably have seen. But what distinguishes Llewellyn's work from these others, and allows us to consider it to a certain extent as his signature, is that his outer border regularly alternates seven round beads with each elongated one, where the engraved forms used a maximum of three or four. This particular device has yet to be spotted on any other manuscript chart.

The scale borders with their foliate terminals and the unusual north-pointer to the compass rose are distinctive features of Llewellyn's work.

Then there are the decorative scale borders with their foliate terminals, one or more of which appear on each sheet. Elements of his work are vaguely reminiscent of one or two of his contemporaries, although none uses quite the same decorative devices. { See (1) Thomas Lupo's Mediterranean chart (c.1600?), British Library Add. MS.10,041; (2) a post-1588 chart of the south Atlantic by 'R.B.', Florence, BNC, Port.30; (3) anon chart (Thomas Hood? c. 1594), British Library Add Ms 17938B; (4) Robert Tindall's chart of Chesapeake Bay, etc, 1608, BL Cotton MS. Aug.I.ii.46; and (5) an unsigned chart of China, 1609, BL Cotton MS. Aug.I.ii.45 [Skelton, 1958, p.168] - respectively Tyacke (2007) pp. 1749-51, nos 33, 34, 45, 63, 64}.

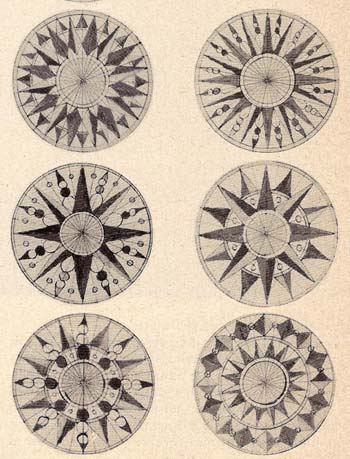

A selection from Llewellyn's many different compass rose centres

But it is in his compass roses that Llewellyn most asserts his independence and at the same time shows us something of his personality. If Llewellyn had been an illuminator of medieval manuscripts, rather than a chartmaker, he might well have been dubbed, 'the master of the compass rose', from his imaginative treatment of this recurring feature. Thirty-five compass roses are distributed over his sixteen charts. Since four is the maximum visible at any one time, Llewellyn could have restricted himself to that number of variations and it is doubtful if anyone would have detected the repetitions. Instead, the conscientious and inventive Llewellyn managed to think up sixteen quite different forms. His permutations are almost Bach-like in their subtlety, ringing the changes around the constant elements of an inner and outer circle, surmounted by an unchanging north-pointer.

"Gulielmus lluellin & Martinus Filij Martini Civis londinensis D.D. Cartas Geographicas patris manu depictas & ab eodem observatas sinus Maritimi in Africa & Asia a Capite bonae Spei ad Regnum China & partem Americae peruanae" [William Llewellyn & Martin, sons of Martin Citizen of London, made the gift of the geographical charts, drawn in the father's hand and according to his own observations, of maritime straits in Africa & Asia, from the Cape of Good Hope to the Kingdom of China and towards South America]Young Martin, who was later to become famous as a physician to Charles II and as a writer, was an undergraduate at Christ Church, possibly in 1634, certainly two years later, and went on to get his BA in 1640. But when was the atlas compiled? Christ Church's records cannot help there and to answer this we must turn to the atlas itself. But how should we begin; what is the accepted procedure for evaluating a whole atlas?

Discounting repeated names on overlapping sheets, Llewellyn's atlas contains some eleven hundred names, far too large a total to be systematically compared with similar columns of place-names from other supposedly comparable charts. And what was comparable anyway? Had Llewellyn died at a ripe old age we might have to study the entire period from, say, 1580 onwards, a span of half a century.

A search for obviously datable features met with no success. The maps of later centuries might reflect discoveries, new surveys or theories, changes in political boundaries, the foundation of cities, the impact of man on his environment; but the East in the late 16th and early 17th century was not responsive to tests of these kinds. True, the turn of the century saw the dramatic replacement of the Portuguese by the Dutch and English, but the presence of a new colonial power would not necessarily stand out on a chart.

What about visual comparison, then? R.A. Skelton warned of basing "a heavy load of theory on a visual impression" [Skelton, 1965 p.6]. Comparison of Llewellyn's outlines for the islands of the East Indies shows them to be at best vaguely similar, sometimes noticeably dissimilar, and never exactly the same as contemporary forms. Visual comparison tends, anyway, to judgements that are both subjective and imprecise.

Another possible point of departure would have been an examination of voyages to the East within the period we have delimited. Again a timely word of warning from Skelton: "Traces of voyages of which the written record is wanting may be found in the maps; and it is equally clear that the maps have suffered a high degree of wastage and loss. In other words, neither the series of voyages, represented by documents, nor the series of maps, represented by extant specimens, is complete" [Skelton, 1965 p.15]. Llewellyn's atlas contains no detected reference to any particular voyage and the spread of place-names is nowhere abnormally dense enough to suggest special knowledge. Since an analysis of Borneo toponymy by Broek confirmed the gap between the acquisition of information about the East Indies and its appearance on charts, this line of approach seemed unprofitable.

Instead it was decided to treat the problem as a strict exercise in comparative cartography. If analysis of all available maps and charts were to reveal certain clear patterns then it would not necessarily matter if the reasons for these remained obscure. They would provide the cartographic evidence we needed to establish a purely cartographic context, against which to evaluate Llewellyn's contribution. Never mind the mistakes and omissions which we, with the benefit of hindsight could detect; Llewellyn was a man of his time and presumably as informed or as ignorant as his contemporaries. Since this cartographic context had never previously been identified, this was clearly where the start had to be made.

A detailed analysis of all sixteen sheets in the atlas was obviously out of the question; there had to be some selection. The precise method hit upon owes something to the techniques of medicine. One area was chosen for intensive study and, rather like a doctor's blood sample, it was hoped that microscopic examination in the laboratory would show up traces of peculiarities infecting the whole. The essential difference, of course, is that the wider relevance of any cartographic findings would have to be checked; they could not, as in the medical analogy, be assumed. But hopefully the range of possibilities would be much reduced.

The area chosen was Java, partly because a pilot study revealed a development in its toponymy not paralleled elsewhere, and partly because its choice by the Dutch as the seat of their government in the East pointed to its special importance in the 17th century.

To confirm the significance of this tentative finding beyond any doubt, an intensive examination was made of charts, maps and globes over the long period 1550-1650. By extending the study beyond the limits of strict relevance a wider picture was revealed and confident conclusions were possible within the chosen period. During the course of this, at least 1,500 Java names were noted. By a ruthless process of compression this vast number was reduced to those sixty-two names which had been included for the first time on maps produced between 1550 and 1620. The period after 1620 is dominated by the entirely new range of names displayed on the charts of Hessel Gerritsz. Since Llewellyn has none of these it seemed sensible to curtail the secondary investigation at this point. Under one head were included all the variant forms of any one name (however much they differed) when they seemed intended for the same place. The incidence of these names on the maps under study could have been arranged graphically at this stage but the scale and complexity would have buried any patterns there might have been. So this analysis was, in turn, put back into the cauldron to distil off still further its essential features. As we were, at this point anyway, concerned only with the presence or absence of a name, not with its spelling, nor with the order in which a sequence of names along the coast was presented on different charts, the first task was to provide each with the date of its first and last appearance. Those that continued throughout the period could be safely ignored and attention focussed instead on those that had been inserted or abandoned.

The result of this survey was a definite confirmation that an entirely new series of Java names began to appear about 1598. These names occur first on a detailed chart of Java, Sumatra and southern Borneo, entitled Nieuwe caerte op Java geteeckent. It was compiled by 'G.M.A.' [i.e. Willem] Lodewijcksz, engraved by Baptista à Doetechum and published at Amsterdam by Cornelis Claesz, probably in 1598. { There is some doubt whether this detailed map was an integral part of the book but f.24v of the French edition includes the note 'Icy doibt estre mis la Carte de Iava & Sumatra', which must surely refer to this. It must be noted, though, that, with the exception of Jacatra, none of the toponymic innovations of the Lodewijcksz map have been detected in the book's text}. Examination of some twenty-five earlier maps compiled in the period up to and including 1598 revealed a consistent total of between fifteen and nineteen Java names. That the greatest number detected, twenty-three, had appeared on a map of c 1540 illustrates the static nature of East Indies cartography in the 16th century. The selection of names was fairly constant too. The forty-nine names that are found on Lodewijcksz's chart would therefore have provided a striking contrast to this traditional, unchanging picture had they merely combined different earlier selections. In fact, two-thirds of Lodewijcksz's total are innovations and his chart thus marks a transfer of initiative from the Portuguese to the Dutch which is, in a cartographic sense, as dramatic and sudden as the changes that were taking place in the geopolitical sphere.

Lodewijcksz sailed with Cornelis de Houtman as supercargo on the first voyage made by Dutch ships to the East. This fact alone provides a strong hint that the new names were gathered then and made known after the expedition's return in the summer of 1597. This is confirmed by Isaak Commelin's account of this voyage, published in Dutch in 1646 and made available in English in 1703. (It is to this latter version that references are made). Commelin's account is quite different from the one issued by Barent Langenes, a few months after the expedition's return. It is also twice as long. Where Langenes had mentioned only one of Lodewijcksz's innovations (and that the most obvious, Jacatra), Commelin refers specifically to fifteen of the thirty-two Java names that Lodewijcksz introduces.

Their source was probably a Portuguese living in Java, Pedro de Tayda [Truide, Taydo, Tayde or de Ataide], whom they met in Bantam (and who is first mentioned on 25 July 1596): "a famous Pilot, who had frequented all the coasts and Islands of the East Indies and made Maps of them all, which he promis'd to shew the Dutch. This gave them great Hopes of discovering more of that Country, than he had discover'd to them before" (Commelin p.156). Hakluyt gives the following account by Barent Langenes [to find this passage, search for 'truide']: "Among the Portingalles there was one that was borne in Malacca, of the Portingalles race, his name was Pedro Truide, a man well seene in trauayling, and one that had beene in all places of the world". De Tayda was murdered three weeks later (16 August) apparently as a direct result of the sharing of his cartographic knowledge with the Dutch. Presumably his maps and pilotage instructions, or copies of them, were taken back to Holland where they would have been gladly received by the publisher, Claesz - much as Bartolomeu Lasso's atlas had been a few years previously. Petrus Plancius, referred to de Tayda in 1598 and in 1599 stated that "it is therefore highly necessary that the masters and commandants read and well consider the writing of Pedro de Tayde and other sailors" [PMC 4:3].

{An alternative explanation would be that the maps brought back by Houtman were compiled in Java, in the course of the numerous discussions de Tayda had with the Dutch. The title of Lodewijcksz's map ends '...delineata in insula Iava, ubi ad vivum designantur vada et brevia scopulique interjacentes descripta a G.M.A.L.' [...was drawn on the island of Java, where the shoals and shallows and intervening cliffs are marked out from life, described by G.M.A.L] - with thanks to Mary Pedley for help with this translation.}

An independent Portuguese source helps to explain simultaneous additions to the toponymy of southern Borneo, not visited by Houtman's ships [Broek]. It also shows why the new names are not Dutch words, which would stand out clearly from the earlier ones, but rather a new selection of indigenous or Portuguese names. However, the inclusion on most maps of the early 17th century of some at least of Lodewijcksz's innovations justifies us in treating them as one of the most important, if not the most important, element in the cartographic context we are attempting to establish. It has not, apparently, been noted before. When considering the dating of charts supposed to have been produced at the end of the 16th century, the inclusion of Lodewijcksz's Java names, therefore, must point to 1597, or more realistically 1598, as their earliest possible date. Llewellyn's atlas includes a number of these names. Indeed, it has one of the largest concentrations of these so far identified. [See the Table of significant Java names].

In a comparable study on the maps of Borneo, already mentioned, Broek [p.148] cites only five maps for the period between Lodewijcksz and Gerritsz's much improved charts of the 1620s, and three of these are versions of Plancius's large world map of 1592, and thus in their content earlier than Lodewijcksz. In the present investigation thirty-four charts, maps and globes of this same period, of sufficient scale to offer at least ten Java names, have so far been identified and examined.

When judged purely quantitatively, the density of Java names in Llewellyn's atlas is only matched by two others: Gabriel Tatton's chart of the region between Bengal and Florida (Biblioteca Nazionale, Florence), provisionally dated to 1600, and Willem Blaeu's wall-map of Asia, one of a series of the continents first produced in 1608. All three contain roughly two-thirds of the thirty-two names introduced by Lodewijcksz. Blaeu's map has in addition a further five names not found earlier, which represent the only significant Java innovations between 1598 and 1620. The new 'Blaeu' names were not known to Llewellyn. After that date Lodewijcksz's names are largely ousted by Gerritsz's and by 1657, when Janssonius issued a detailed chart of the island, only seven remained.

As an indication of possible refinements to these generalisations a few specific examples will have to suffice:

The outline commonly given to Java was essentially indefinite, since its south coast was unknown. Van Linschoten, indeed, had even questioned whether Java was an island at all. Despite the fact that Houtman's fleet returned by way of the south coast - the first European vessels known to have circumnavigated the island - there was no measurable improvement in the island's shape. It was left to Gerritsz (evidently on his engraved chart of 1618) to replace this shapeless mass with an outline that is strikingly close to its real form.

|

It is possible that Llewellyn also sailed with De Houtman. His chart of Java (top) perpetuates the shapeless island that the Portuguese depicted on their charts and predates the remarkably modern outline produced by Dutch hydrographer Hessel Gerritsz. in 1618 (middle). |

So much for the context - how does Llewellyn fit into it?

When Llewellyn's version of Java is measured against all the features which the analysis had shown to be significant, it falls naturally into a slot close to the beginning of the Dutch period. Eight of Lodewijcksz's new Java names seem to disappear after 1600, yet all are to be found in Llewellyn's atlas. One special instance can be mentioned. Arosbaja, at the west end of Madura Island, is conveyed by Lodewijcksz as Rossumbaya. This is clearly a mistake and it was to be corrected by Blaeu in 1608. But Llewellyn and Tatton both repeat Lodewijcksz's error. These three charts are bound even closer together by the inclusion of three names not traced anywhere else: Chuconin, Labuan, Meleasseri [see the Table of significant Java names].

While Lodewijcksz's seems clearly to be the mother-chart that introduces the period of Anglo-Dutch dominance in the East, Llewellyn's picture of Java is far from being a slavish copy of it and several of the name forms are noticeably dissimilar in the two versions. Beyond that, Llewellyn includes one name not found on Lodewijcksz's chart, nor, apparently, on any other, Sigulo, just east of Jakarta. [Update, January 2014. Smith (2011, p.108) points out that Agua de S.Igido and Agua da Sigida are found on charts of the 1560s and 1570s, for example one of 1576 attributed to Fernão Vaz Dourado, which contradicts the point made about sigulo.] It is also significant that Llewellyn's Juama (for Lodewijcksz's Ivanna) is the spelling adopted in the 1703 Commelin account (p.197). Tatton's Java names can all be found, with minor variations, on Lodewijcksz's chart, and Blaeu's map of 1608 is even closer to the latter.

But the essential individuality of Llewellyn's work shows that we are dealing with an important new source. None of the contemporary Dutch charts that I have been able to examine, by Cornelis Doedtsz, Everts Gijsberts and the brothers Harmen and Marten Jansz, all members of the so-called Edam School of chartmakers, reflect to anything like the same degree the new generation of Java names, and some remain entirely ignorant of them.

There is not space to mention more than the barest details of parallel studies into other sections of Llewellyn's atlas. The greater part of the impact of Houtman's voyage (or perhaps more properly of de Tayda's knowledge) was expended on Java but ripples reached Borneo and Sumatra at least, adding a further four new names for the former and a possible eleven for the latter. Llewellyn includes all but one of these. In no case does his information seem to conflict with a 16th-century date.

|

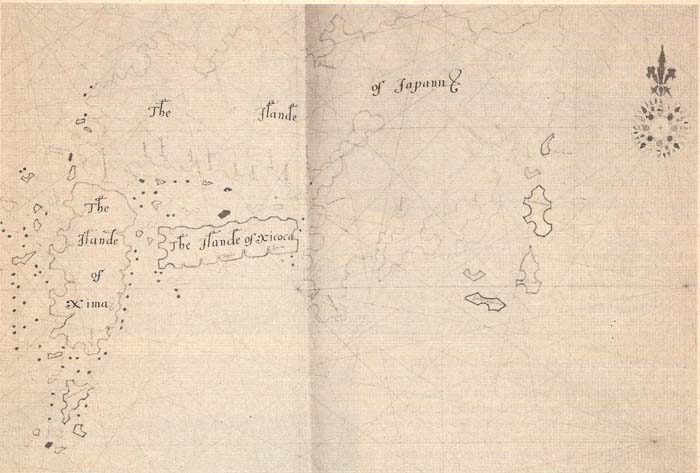

Detail of Japan from the atlas |

Attention was also paid to the shape of Japan. In 1595 Ortelius had added to his atlas Luis Teixeira's picture of Japan, an immeasurable improvement on its grotesque predecessors. Manuscript charts, in particular, were slow to adopt this and it is therefore significant both that Llewellyn should favour Teixeira's form and that his distinctive variation of it precludes his having copied the engraved map. Llewellyn's Dutch contemporaries, meanwhile, persevered with the Vaz Dourado form of half a century earlier, as did Tatton.

|

1 Lodew. East Ind. 1598? |

2 Lodew. World 1598? |

3 v.Langren Asia 1598? |

4 LLEWELLYN ATLAS 1598? |

5 v.Langren World 1600? |

6 Tatton 1600? |

7 Merc-Hon E. Indies 1606 |

8 Blaeu |

9 Lavanha Java 1615 |

10 Gerritsz Java &c 1628 |

|

Brandaon |

Brandao |

- |

Brandicon |

Brandaon |

Brandaen |

Brandaem |

Brandan |

- |

Bronden |

|

Buama |

- |

- |

Buania |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Cangabaya |

- |

- |

Cangabaya |

Cangabaya |

Cangabaia |

Cangalaia |

- |

- |

- |

|

Chandana |

- |

- |

Chandana |

- |

- |

- |

Chandana |

- |

C.Sandana |

|

Charita |

Charica |

- |

Charita |

- |

Charita |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Cheregin |

- |

Cheregin |

Cheregin |

Cheregin |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Cherola |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Cerela |

- |

- |

- |

|

Chuconin |

- |

- |

Chuconin |

- |

Chuconim |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Daya |

- |

- |

Daya |

Daya |

Daya |

Dasa |

Daya |

- |

- |

|

Der Mayo |

Der Mayo |

Dermaijo |

- |

Der Mayo |

Der Mayo |

Deretmayo |

Der Mayo |

Dermaino |

- |

|

Dugumala |

- |

Dugumala |

Dugumala |

- |

Dugumala |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Gerrici |

- |

Gerrici |

Gertici |

Gerrici |

[Gerrici] |

Gornici |

Gerrici |

- |

- |

|

Iacatra |

- |

Iacatra |

Jacatrall |

Iacatra |

Jacatra |

- |

Iacatra |

- |

- |

|

Joartaon |

- |

- |

[Joram] |

- |

[Joartaon] |

Zaartaon |

Iortan |

Ioartam |

Jortan |

|

Issebongor |

Essebonque |

- |

Issebongor |

- |

Essebonque |

- |

Issebongor |

Issebongor |

- |

|

Issefucar |

- |

- |

Issefucar |

- |

Essofucar |

- |

Issefucar |

Issefucar |

- |

|

Iunculan |

- |

- |

Sunculam |

- |

Sunculan |

- |

Iunculan |

Iuncula[n] |

- |

|

Ivanna |

- |

- |

Juama |

- |

Juanna |

Zuama |

Inuana |

- |

- |

|

Labuan |

- |

- |

Sabuane |

- |

Labuan |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Lassaon |

Lasseo |

- |

- |

Lassao |

Lassaon |

Lassaon |

Laisem |

- |

Lassem |

|

Madura |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Madura |

- |

- |

|

P.Maniavac |

- |

- |

P.Manivac |

Maniavac |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Mataran |

- |

- |

- |

Mataran |

- |

- |

Mataran |

Mataran |

- |

|

Meleasseri |

- |

- |

Meleasseri |

- |

Meleasseri |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Monucaon |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Memucaon |

Memucaem |

Monucaon |

- |

- |

|

Punctan |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Pondang |

Pontung |

|

Rossumbaya |

- |

- |

Rossumbaya |

- |

Rossumbaia |

- |

Arosbay |

- |

Arosbay |

|

Sura |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Sura |

- |

- |

|

Surubaya |

- |

- |

Surabaia |

- |

Surubaia |

- |

Surrabaia |

Surubaia |

Sourrabaya |

|

Taggal |

- |

- |

- |

Taggal |

Taggall |

Taggal |

Tatagalle |

Taggal |

- |

|

Tanhara |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Janhara |

- |

Tanhara |

- |

- |

|

Tanjonjava |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Tanjonjava |

- |

Tanionava |

- |

- |

|

New: 32 |

5 |

5 |

21 |

11 |

23 |

11 |

21 |

9 |

7 |

|

Total: 49 |

11? |

16 |

40 |

23 |

41 |

21 |

42 |

31 |

92 - south |

Details of the maps analysed:

On the above, in general, see Schilder

Later that year, de Houtman spent a month on Madagascar, at what they named Hollandsch Kerkhof (now Nosy Manitsa), where several crewmen were buried. Llewellyn does not include that or any names that can be associated with de Houtman [personal communication from James Armstrong, June 2006].

Indeed, with the present state of knowledge it seems that the Llewellyn atlas carries no direct evidence of that Dutch voyage, besides the de Tayda information it brought back. The atlas is based throughout on Portuguese work, even if nothing like it has survived.

W.A.R. Richardson (2006, 1991, 1989), in his analyses of the process of toponymic corruption, has demonstrated how the Lodewijcksz chart (and likewise the relevant sheet of Llewellyn's atlas) turn two small rivers in Sunda Strait and the westerly peninsula into three imaginary towns (Jssebongor, Issesucar, Juncalan) arranged along a mythical south-inclining Java coast. Richardson describes how 'two charts, on different scales and partially overlapping, were joined at a completely wrong angle by a compiler' (1989, p.9). This presumably provides evidence of how the de Tayda information was bolted onto the standard Portuguese outline. Richardson illustrates Java and the islands to its east (2006, fig.26), and (p.71) notes that Llewellyn 'has most of the same Sunda Strait names [as on Lodewijcksz], although wrongly sited on Java's north coast between Bantam and Jacatrall [Jacatra]'. This may indicate that the Dutch received notes or verbal information instead of charts from de Tayda [the account said only that he had 'promised' to show them charts], which caused this confusion. It is unlikely that de Tayda did not himself understand the local geography.

For the earlier report, see Heidi Brayman Hackel and Peter C. Mancall, 'Richard Hakluyt the Younger's Notes for the East India Company in 1601: a Transcription of Huntington Library Manuscript EL 2360', Huntington Library Quarterly 67, 3 (2004): 423-36 (transcription pp.432-5); for the slightly later version from the Company archives the most accessible transcription is in John Bruce, Annals of the honorable East-India Company, 3 vols (London, 1810), 1:115-21, available via Google Books. While the list of 'authors and witnesses' he cites includes references to the surviving crewmen of some previous voyages, there is no entry that could plausibly be construed as a reference to Llewellyn. However, if Llewellyn was a survivor of the de Houtman voyage (and conceivably the Raymond and Lancaster expedition as well) it seems highly likely that Hakluyt would have sought out the Steward's first-hand account of a voyage so important for English planning, particularly the details of the working of the Bantam pepper market. The relevant section of his report listed as sources the 'Englishmen that haue bin personallie in the Molucos, Jaua and in manie places of ye Portingale Indies'.

In February 1601 Hakluyt was paid for supplying three maps, whose identity is still a matter for conjecture. [An earlier commentator, confused by the use of Hakluyt's alternative name, Hackett, attributed this incident to 'Alderman' Hackett.]

Coincidentally, Hakluyt had been at both Westminster and Christ Church [like Martin Llewellyn Jr (who was born in the year of Hakluyt's death) and perhaps also Martin's unknown patron some time before].

"Sir Thomas Smythe (Smith), Haberdasher. Farringdon Without 1599-1601; 1604.

Sheriff 1600-1. Elected

Sheriff 1587.

Knighted 13 May 1603; M.P. Dunwich 1604-11, Sandwich 1614, Saltash 1620-2; Receiver

Duchy Cornwall 1604; Ambassador to Russia; Auditor 1597-8; Treasurer St. Bartholomew's Hospital 1597-1601;

Committee E.I.C. 1600-1, 1603-22 (Governor 1600-1, 1603-5, 1607-21); Governor Russia Company; Treasurer

Virginia Company 1600-20; Master Haberdashers 1583-4, 1588-9, 1599-1600. Died 4 Sep 1625; Will (PCC 107

Clark) 31 Jan 1622; proved 12 Oct 1625."

From other sources the following can be added. That Smythe went as trade commissioner to negotiate with the Dutch in 1596 (when he would certainly have learnt about de Houtman's voyage) and 1598; that Thomas Hood taught mathematical geography and navigation at his house in the 1580s; and that in 1616 Smythe engaged Edward Wright to lecture to the East India Company on navigation and mathematics.

A man, then, of considerable standing in the City of London, whose consistent interest in navigation and foreign trade led to his being chosen as the first Governor of the East India Company at its foundation in 1600.

His involvement with St Bartholomew's Hospital was also long and deep, although the details remain unclear. Beaven includes the ambiguous passage: "Auditor 1597-8; Treasurer St. Bartholomew's Hospital 1597-1601". The Barts Archives apparently cannot confirm that statement, although there is a record that Thomas Smythe 'haberdasher' was a governor and almoner of the Hospital. At his death in 1625 he left them £640, the largest of his legacies. The Sir Thomas Smythe Charity was set up, presumably with that sum, and was certainly extant in 1923.

In 1603 [1604 New Style?] Llewellyn borrowed the large sum of £100 from Smythe, to be paid back personally on the following 22 February at Smythe's house [British Library Egerton Charter 7293]. In 1607 he signed a second bond with Smythe [Egerton Charter 7328], concerning an executorship involving Llewellyn's brother Maurice and somebody called Wheeler [possibly Ambrose Wheeler, one of those who signed a bill of adventure in the East India Company in 1601-2].

It is against that background we should view the meeting on 27 August 1597, at which Llewellyn's request for the post of Hospital Steward was accepted (for an unspecified future date) and he was immediately awarded the lesser post of Renter. The meeting, which was not a general court of governors, was attended by just nine individuals. They are not in alphabetical order but the first named is Thomas Smythe [he was to be knighted five years later]. Does that mean he was in the chair? And was he then the Hospital Treasurer [Beaven dates his appointment to that same year]? [As an aside, two of the others who attended that 1597 meeting, John Newman and William Quarles, were 1601-2 EIC 'Adventurers', as also was 'Morrice Llewellin' - see 'British History Online.]

None of the above weakens the growing body of circumstantial evidence pointing to the likelihood that Smythe was Llewellyn's patron in 1597. They certainly remained in contact for at least the next ten years. If this proves to be the case, the most likely reason, surely, would be that Llewellyn possessed materials from which an atlas could be constructed of the region to the east of the Cape of Good Hope that was of particular interest to the first English Fleet.

[For help with the above note thanks are due to Sarah Tyacke and Katie Ormerod, Deputy Archivist, St. Bartholomews' Hospital Archives & Museum].

The first two noteworthy English voyages to the East were both made by James Lancaster, but the first (1592) never reached Java and the second (1601-3) was too late to have involved Llewellyn personally. Only one recorded voyage could have produced the information about Java set out by Llewellyn and, simultaneously, have been completed by summer 1597, and that was Houtman's. Dr Kerling discovered in the Hospital's records that on 27 August 1597 Llewellyn had applied in person for the stewardship of St Bartholomew's Hospital. It is the date that is vital here since it falls just two weeks after Houtman's vessels reached Amsterdam with their eighty-nine survivors, on 11 and 14 August respectively {elsewhere the figure for survivors was given as 87 - there does not seem to be a crew list}.

If Martin Llewellyn was not one of the 249 men under Houtman's command how else can we explain his sons' statement in Christ Church's Donors' Book that the atlas had been drawn "according to his own observations"? Do we see in Llewellyn a young man, chastened by his experiences, settling for a secure job ashore after an extremely hazardous voyage? Direct evidence that he accompanied Houtman is still wanting but the idea of an Englishman sailing with the Dutch need not stretch the imagination. Two of the four Dutch fleets that set sail to the East in 1598 had English pilots aboard.

When the few clues to Martin Llewellyn's identity were followed up they led, step by step, to the happy discovery that he had spent what must have been almost his entire working life in one place. When he had applied for the Steward's post in August 1597 a promise was clearly made to him. This was fulfilled in July 1599, when he presented himself to the Hospital Governors to hear that he had been appointed as their Steward. But, on the earlier occasion, he had been granted the post of Hospital Renter, with immediate effect. Initially, he held both posts and, after 1607, just that of Steward, in which position he remained uninterruptedly until his death in 1634. The value of this for our purpose is that his day-to-day duties associated with the collecting of rents and, as Steward, the requirement to 'supervise the victuals, and the admission and discharge of patients' - would have been incompatible with any voyage abroad after 1597, if the almost annual succession of children born to him between 1606 and 1623 was not even more potent evidence [recorded in the parish records of St Bartholomew the Less]. {Dr Kerling pointed out that, as the Hospital's rent-collector between 1597 and 1607, his name appears at the head of the accounts. Had he been absent in that period, leaving a deputy in place, she thought that the second name would have been mentioned as well. Bernard Quaritch had for sale a volume of receipts for rent paid to the Hospital by Sir Richard Saint-George, 1601-14, each signed by Llewellyn, half yearly initially and then quarterly until the end of his time as Renter/Receiver {listed on the web in 2006 at < http://www.polybiblio.com/quaritch/EW399.html >; not there February 2008}. As further corroboration, Dr Kerling also noted that the Governors' complaint of 1604 was directed at him personally}.

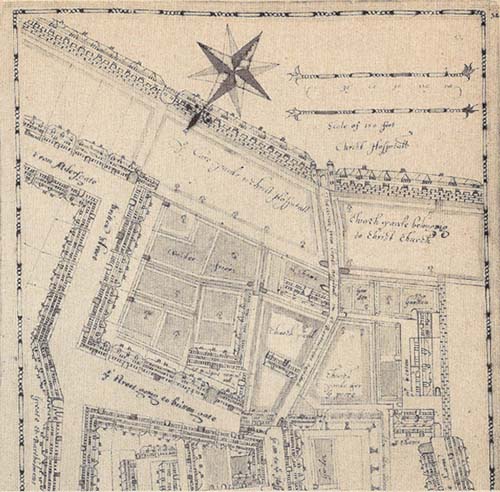

Llewellyn was Steward of St Bartholomew's Hospital from 1599 until his

death in 1634. Distictive scale borders and the outer frame suggest that an anonymous plan of 1617 in the

Hospital's Repertory Book was also his work. Further evidence for Llewellyn's authorship of the Repertory Book

plans comes from a comparison of the handwriting found in the atlas with that on one of these plans.

His growing family could well have been the cause of his perpetual state of debt [see His finances below], which involved him at one time in a dispute with William

Harvey, the discoverer of the circulation of blood. Somewhere there may be lurking some clue that will

eventually link the two spheres in which Martin Llewellyn operated, as chartmaker and Steward. One

possible bridge is provided by a series of estate plans, a few of them dated 1617, in the Hospital

Repertory Book, some of which betray his characteristic style. {On these, see Moore 2:257-60;

some of these plans are among those issued by the London Topographical Society, in their 'Maps, Plans

and Views' series, nos 84, 87 (1950, 1954), on which see also Judith Etherton, 'New evidence - Ralph Treswell's

association with St Bartholomew's Hospital', in: A.L. Saunders (ed.) London Topographical Record 27 (1995)

pp.103-17 (Publication No. 149)}. One of these plans is

evidently referred to in the payment to Llewellyn in 1613-14 of 3s 4d "for drawing a platt of the

precinct of this parish" (Churchwardens Accounts). While his charts betray the work of a trained

draughtsman, these further finds illustrate his versatility. {For a listing of the various

written surveys and plans see the entry for St Bartholomew's Hospital Archives and Museum in the

Access to Archives (under 'Description:' then 'Particular of Lands')}.

Fresh information concerning Llewellyn’s estate surveys is set out in Dorian Gerhold’s London Plotted: Plans of London Buildings

c.1450-1720, London Topographical Society, Publication No.178 (2016), see particularly the ‘Introduction’ and the detailed

notes on Plans 19, 20 and 21. This confirms that, while Llewellyn certainly copied some of the plans from the work of others, those

directly relating to the Hospital were actually surveyed by him. Though not always topographically accurate, they were drawn to

scale.

Gerhold introduces the unexpected information that Llewellyn had also made at least two relief models, which, as the

author points out, helps explain why the 1617 plan of St Bartholomew the Less (his Plan 21) shows the lower parts of the walls as

if folded flat onto the ground ‘exactly as a model-maker might do it’. {These two paragraphs added 5 December 2016}

Further than that, biographical details are yet to emerge. Clues may lie in the relationships

with those to whom he owed money (see next section) or the wider range of his Associates. For a man on an annual salary of £10 to have

incurred debts of many times that figure, and to have had the support of rich and influential

figures, suggests there are important facets of his life of which we still know nothing.

Despite the embarrassment he must have caused the Governors, his 35-year term as Steward was

the longest in the Hospital's history.

{Since financial matters, usually difficulties, provide most of what we know about Llewellyn, it is worth tabulating the public record systematically. As background, it can be noted that, as Steward, he was handling about £100 a month, against his annual salary of £10 [Moore, 2:229], though clearly he must have had other sources of income.

[See, where appropriate, His associates]

To date, the earliest known English sea charts of the East belong to a series by Gabriel Tatton, unearthed in the Admiralty Library {later Hydrographic Office, Taunton; now Portsmouth Naval Museum, Admiralty Library Manuscript, MSS 352} by Sarah.Tyacke. They have been dated to 1620-21 [see Tyacke, 2008]. Robert Dudley's Arcano del Mare of 1646 had previously been considered the earliest sea atlas by an Englishman. {Coincidentally, Dudley had been at Christ Church (from 1588)}. Even if Llewellyn had made his fair drawings in, say, 1615, this would not invalidate the claim that the charts belong, as far as their contents are concerned, to the previous century and are thus by a clear margin the earliest English ones of their kind.

A crucial diagnostic tool is described in the Analytical methods section. Having defined what was called the 'cartographic context' - part of but distinct from the historical context - this was applied to the toponymy of the north coast of Java. This established a close link with an unsuspected legacy of the first Dutch voyage to the East Indies, namely a sequence of new names. Later, the Dutch would transform the cartography of Indonesia but Houtman's contribution related more to place-names than to improved coastal outlines. It is evident that this information came from an independent Portuguese source. Pedro de Tayda was already known to history, though as little more than a name. Now for the first time the detail of his cartographic signature can be documented. Just as de Tayda seems not to have previously shared his much-admired knowledge with his Portuguese countrymen, so his murder [the first example of a cartographic killing?] removes the possibility that his information could have been brought back by a later voyage. No trace has been found in the Llewellyn atlas of any information dating from later than 1597 [though, of course, future research might contradict that]. The toponymic innovations of Blaeu and Gerritsz (1608 and 1628) are absent. Nor does New Guinea have any reference to the discoveries of Torres and Le Maire (1606 and 1616). Further anchoring the atlas to the beginning of its possible date-range is the fact that it includes names that were to disappear from the cartographic bloodstream shortly thereafter.

That I have risked offence by claiming a man with so Welsh a name for England is due to an absence, so far, of any evidence linking him directly with Wales. He lived the greater part of his life in London (as the longest-serving Steward in the history of St Bartholomew's Hospital), gave names to his children [Anne, Anthony, Gabriel, Henry, John, Martin (twice), Morris, Richard, Robert, Thomas, William] that show him to have been in practice, if not in origin, an Englishman, and was buried in St Bartholomew's the Less, London. The compromise term, British, is both cumbersome and inaccurate.

I wonder if Christ Church had any idea of the extraordinary coincidence involving two items they received, apparently in 1634. Alongside the classics and theology that fill most of the pages of their Donors' Book, they recorded two consecutive, but apparently unconnected, gifts of, respectively, Llewellyn's atlas and "Wagenars Mirrour of Mariners", or, in other words, the English translation of Waghenaer's Spieghel der Zeevaerdt, which appeared in 1588 as the first sea atlas to be produced in England. A bumper cartographic year indeed for Christ Church. {For a note about the donor of the Waghenaer atlas, John Gofton, see under the Associates}.

Unlike Waghenaer, Llewellyn seems to have had no influence on the development of marine cartography, since his atlas clearly remained in his possession, and no other version is known. The possibility remains, though, that Llewellyn was involved in some way in the early days of the East India Company. He would presumably have had information of value to those planning a voyage to the East. Certainly his brother, a founding investor in the new company, and its first Governor, Sir Thomas Smythe, were among those to whom he owed money. But, in the absence of any surviving charts directly associated with the early years of the East India Company, Llewellyn's atlas provides a glimpse into the practical cartographic knowledge that could have been available to those Englishmen who first sailed to the East under the Company's aegis. In a wider sense, it must rank as the closest surviving manuscript to the all-important first voyage of the Dutch, an event that signalled the twilight of the Portuguese empire and the simultaneous births of the Dutch and English successors to it. The detail contained in his charts and the fact that Llewellyn evidently voyaged to the East himself combine to assure his atlas a prominent and authoritative place in any future cartographic studies of the East.

[Reference is made to the new Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [Oxford DNB], accessible free online for UK public library subscribers. See, where appropriate, His finances]

Barber, Peter, 'Map-making in England, ca. 1470-1650', in: David Woodward (ed.) The History of Cartography, Volume 3, Book 2 (University of Chicago Press, 2007), p.1652, note 464.

Barker, G.F. Russell and Alan H. Stenning, The record of old Westminsters (London, 1928) 2:585 [on Martin Llewellyn junior].

Bendall, Sarah, Dictionary of land surveyors and local map-makers of Great Britain and Ireland 1530-1850, 2nd ed. 2 vols (British Library, 1997) [Llewellyn is not included].

Broek, Jan O.M., 'Place names in 16th and 17th century Borneo', Imago Mundi: the International Journal for the History of Cartography 16 (1962): 129-48.

Campbell, Tony, 'The Drapers' Company and its school of seventeenth century chart-makers', in: Helen Wallis & Sarah Tyacke (eds), My head is a map: essays & memoirs in honour of R.V. Tooley (London: Francis Edwards & Carta Press, 1973): 81-106.

Campbell, Tony, 'Martin Llewellyn's Atlas of the East (c. 1598)' [unpublished paper presented to the International Conference on the History of Cartography, Greenwich, 7-11 September 1975]

Campbell, Tony, 'Atlas Pioneer', Geographical Magazine 48:3 (December 1975) pp.162-7.

Campbell, Tony, 'Martin Llewellyn's Atlas of the East: a mystery partly unravelled', Christ Church Library Newsletter 5, 2 (Hilary 2009), pp.1, 7-10. [A summary of what is found on this webpage.]

Commelin, Isaak, A collection of voyages undertaken by the Dutch East-India Company (London, 1703) [translation of the 1646 Dutch text].

Durand, Frederic & Richard Curtis, Maps of Malaya and Borneo: Discovery, Statehood and Progress (Editions Didier Millet & Jugra Publication, 2014). [Not seen.]

Gerhold, Dorian. London Plotted: Plans of London Buildings c.1450-1720, London Topographical Society, Publication No.178 (2016).

Lodewijcksz, G.M.A.L. Premier livre de l'histoire de la navigation aux Indes Orientales par les Hollandois (Amsterdam: Claesz., 1598).

Moore, Sir Norman, The history of St Bartholomew's Hospital, 2 vols (London, 1918).

Notes and Queries, series 3, volume 1 (Jan-June 1862) p.28. [About earlier Llewellyns]

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [the revised and extended DNB is available online to subscribers, or free to users of the UK public library network].

Payne, Anthony. Hakluyt & Oxford. Essays and Exhibitions marking the Quatercentenary of the death of Richard Hakluyt in 2016 (London: Hakluyt Society, 2017). [Catalogue note to the exhibition at Christ Church, Oxford, 'Richard Hakluyt and Geography in Oxford 1550-1650', October 2016 to January 2017, pp. 85-7.]

PMC. Armando Cortesão & Avelino Teixeira da Mota, Portugaliae Monumenta Cartographica, 6 vols (Lisbon, 1960). A second reduced edition ([Lisbon]: Imprensa Nacional - Casa da Moeda, 1987) with corrective addenda by Alfredo Pinheiro Marques.

Richardson, William A.R., The Portuguese discovery of Australia: fact or fiction? (Canberra: National Library of Australia, 1989) p.9.

Richardson, William A.R., 'The origin of place-names on maps', The Map Collector 55 (Summer 1991): 18-23, especially 20.

Richardson, William A.R., Was Australia charted before 1606: the Jave la Grande inscriptions (Canberra: National Library of Australia, 2006), pp.70-1, fig. 26 (detail of Llewellyn's Java etc). [Including a comparison between the Lodewijcksz and Llewellyn names.]

Schilder, Günter, Monumenta Cartographica Neerlandica Vol. VII. Cornelis Claesz (c. 1551-1609): Stimulator and driving force of Dutch cartography (Alphen aan den Rijn: Canaletto/Repro-Holland, 2003). ISBN 90 6469 765 5 [and other volumes, e.g. Vol. IV for the 1608 Blaeu wall-map of Asia].

Shirley, R.W., The mapping of the world: early printed world maps 1472-1700 (London: Holland Press, 1983 [and later editions]).

Skelton, R.A., Explorers' maps: chapters in the cartographic record of geographical discovery (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1958).

Skelton, R.A.,'Looking at an early map', University of Kansas Publications, Library Series, 17 (Lawrence: University of Kansas Libraries, 1965).

Smith, F. Andrew & Hilary F. 'What really was "the Kingdom of Hermata" in West Borneo', Borneo Research Bulletin 42 (2011): 104-10. [with new insights in the Java names in the atlas.]

Smith, Thomas R., 'Manuscript and printed sea charts in seventeenth-century London: the case of the Thames School', in: Norman J.W. Thrower (ed.) The compleat plattmaker: essays on chart, map, and globe making in England in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (University of California Press, 1978): 45-100.

State Papers - Colonial. East Indies, China and Japan [entries 281 and 288 re Morris Llewellyn and the East India Company, 1600 and 1602].

Stevens, Henry, Dawn of British trade to the East Indies as recorded in the Court Minutes of the East India Company 1599-1603 (London, 1886) [re Morris Llewellyn].

Tyacke, Sarah, 'Chartmaking in England and its Context, 1500-1660', in: David Woodward (ed.) The History of Cartography, Volume 3, Book 2 (University of Chicago Press, 2007), pp. 1722-80.

Tyacke, Sarah, Gabriel Tatton's maritime atlas of the East Indies, 1620-1621: Portsmouth Royal Naval Museum, Admiralty Library Manuscript, MSS 352, Imago Mundi: the International Journal for the History of Cartography 60:1 (2008) pp. 39-62.

Wieder, F.C. Monumenta Cartographica. 5 vols (The Hague, 1925-33).