(main menu)

CAMPBELL

articles

SITEMAP

site is

ABOUT

NEW

|

(main menu) |

CAMPBELL articles |

|

SITEMAP |

site is ABOUT |

NEW |

|

The development of lettering and numeral punches in fifteenth-century Italy, as a semi-mechanical alternative to the engraver's burin, marks a little-known point of contact between the histories of engraving and cartography. 1 One of the unique features of a map is its necessarily dense toponymy, requiring the time-consuming skills of an experienced lettering engraver. Very early in the history of printed maps, indeed during preparation of the first set of maps to be engraved (if not quite the first to be published), punching was devised as a labour-saving alternative.

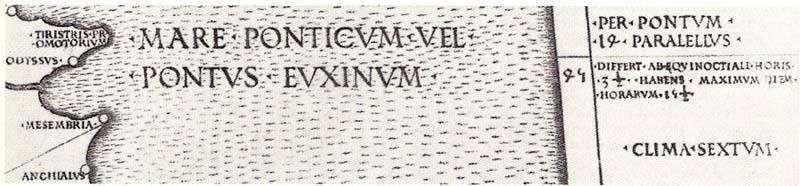

Fig.113. Claudius Ptolemy, Cosmographia, Rome 1478, detail from 'Nona Europae Tabula' showing three sizes of punched lettering (London, British Library, Maps C.1.d.3).

Conrad Sweynheym does not expressly claim responsibility for inventing punched lettering. But the dedication to the 1478 Rome edition of Ptolemy's Cosmographia (or Geographia), which appeared the year after his death, referred to the three years (i.e. 1474-77) during which, 'calling on the help of mathematicians, he gave instruction in the method of printing [the maps] from copper plates'. 2 On this passage and the evidence of the engraved maps which Arnoldus Buckinck issued after Sweynheym's death, hangs the German-born printer's claim to a technique that would be used fairly widely on Italian maps for the next century or more.

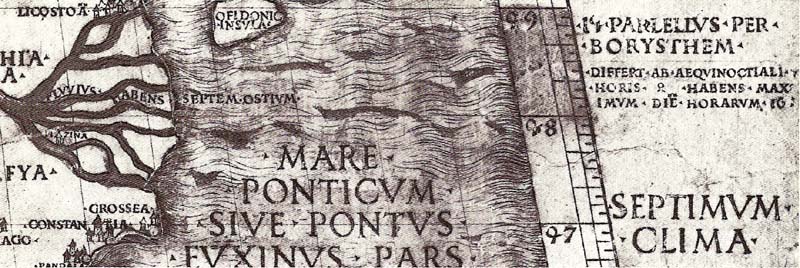

No punches from Sweynheym's sets or any other survive - at least none is recognized as such. Nor has punched work of this kind been identified on any surviving copper plate. Evidence for the appearance of the punches, their method of application, their proliferation, the incidence of their use and the places where they were found, must all derive, therefore, from impressions pulled from punched plates. To this end, a thorough study has been made of fifteenth-century maps, but sixteenth-century work remains to be systematically examined. All the instances that have been identified so far involve Italian work. 3 Besides the twenty-seven maps in the Rome Ptolemy (fig. 113), the technique can be seen on two other maps assigned to the incunable period. The so-called Eichstätt Map of northern and central Europe by Nicholas of Cusa, insecurely dated 1491 (and certainly produced in Italy, rather then Eichstätt as its inscription appears to suggest), 4 displays the evident use of Sweynheym's punches (fig. 114).

Fig. 114. Nicholas of Cusa, 'Quod picta est parva Germania tota tabella' (the Eichstätt Map), Italy, late 15th century? Detail showing use of the same three sizes of letter punches as in fig. 113, with an additional smaller fount (London, British Library, Maps C.2.a.1.).

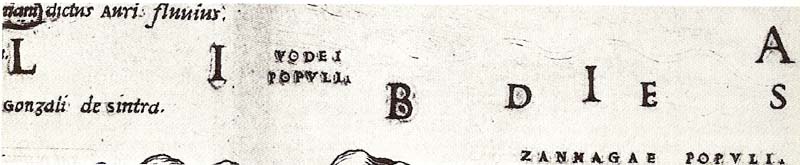

The last of the early examples is a Ptolemaic world map of uncertain date and origin, though clearly Italian and apparently produced in the fifteenth century. 5 A sampling of sixteenth-century Italian work - no more has yet been attempted - identifies the technique as recurring throughout the century, with the latest instance being Livio Sanuto's Venetian atlas of Africa, issued in 1588 (fig. 115). Nevertheless, in another context, that of music printing, the process of punching the notes into a pewter plate is still continued today.

Fig. 115. Livio Sanuto, Geografia dell' Africa, Venice 1588, detail from 'Africae Tabula I' showing three sizes of punched lettering and handcut italic (London, British Library, Maps, C.21.c.6).

Punched lettering seems to have been restricted to maps. The main purpose of this note is to alert the historians of engraving to the possibility that the letter-puncher might have crossed the narrow divide separating the cartographic engraver from his counterpart working on reproductive prints. To assist in the identification of this technique and as a complement to the illustrated details, the following features associated with punched lettering can be itemized:

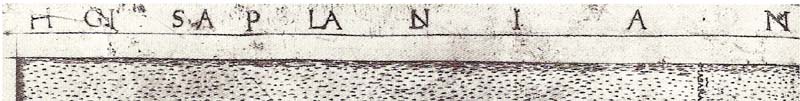

Fig. 116. Francesco Berlinghieri, Geographia, Florence. [1482], detail of the handcut title 'Hispania Nova', the first word of which has been carelessly altered from 'Gallia' (London, British Library, C.3.d.10.).

It is not so surprising that it should have been a printer who developed letter and numeral punches. The use of metal stamps or dies would have fallen well within Sweynheym's experience, since steel punches were employed in forming the matrix (or mould) from which printer's type was cast. Punch-cutters were experienced in cutting an individual piece of type in relief on the end of a steel punch. They, or the matrix-maker, would have been thoroughly versed, too, in the art of hammering that punch with a consistently strong blow into a block of copper, although this technique must have needed modification when dealing with the much thinner copper-plate.

The more fundamental difference between the two applications is that the punches for map lettering would be unusual in having each letter cut the right way round (right-reading), so that a reversed image would be transferred to the copper-plate, for that, in turn, to be righted in printing. Conversely, punches cut by a punch-cutter for casting into type would require wrong-reading lettering, as would those for use by a goldsmith or book-binder. The punches for the purpose that concerns us would therefore have had to be cut specially; there was no other obvious use for them.

Despite the relatively small number of instances so far detected, the century or so that spans the observed Italian examples suggests that we are dealing with a formalized and continuous practice, probably transmitted through some kind of training and possibly with its own manuals of instruction. In a purely fifteenth-century context, the identified punches range from various sizes of lettering and numerals to stars and arrangements of town symbols imaginatively used on the Eichstätt Map. In later centuries, punches reappeared intermittently and for a variety of features. That relatively few publishers after Sweynheym's time thought fit to employ punches for lettering - the most time-consuming and complicated part of a map engraver's work - has a number of possible explanations. The equipment and highly specialized skills needed to use it may simply have been unavailable. Alternatively, the saving of time may have proved illusory, or others may have shared the aesthetic qualms of a much later commentator, Diderot. 8 It is not impossible, though, when contrasting the size and range of fifteenth-century punches with the difficulties encountered by later practitioners, that some of the skills of Sweynheym's puncher died with him.

It should not be thought that there is any originality in these observations on punched lettering; this is just a prime example of the interrupted transmission of knowledge. The first known reference in print to the use of lettering punches was a note by Wilberforce Eames, made a century ago. 9 While discussing the maps in the 1478 Rome Ptolemy, he pointed out that the inscriptions were not 'engraved but were made with a punch and mallet'. This discovery remained largely unnoticed. The authority on engraving, A. M. Hind, praised the lettering on the assumption that it had been hand-cut, 10 although he acknowledged his error on being shown some enlarged photographs by Hinks in 1943. 11

The subject of punched lettering on maps is sufficiently important to justify a thorough investigation by a printing historian. Woodward has highlighted the potential that can be anticipated from a study of this technique:

'Since these punches create a constantly consistent image which can usually be readily identified whenever they are used, it is theoretically possible to trace the use of a given set of punches from map to map. The life history of these punches should help in identifying engravers and place of publications by acting as an engraver's trade mark as eloquent as his initials.'12References: